CBT Treatment in Melbourne: A Practical Approach to Change Patterns of Thinking, Feeling & Behaving

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used psychological treatments offered by psychologists in Melbourne and across Australia. In this post, we’ll walk through some of the foundational principles of CBT, how it works in practice, some of the common thinking errors or ‘traps’ and how CBT can help to change these. Finally, we’ll highlight what CBT can’t do, because no single approach is perfect, and CBT isn’t always the right fit for everyone.

What is CBT?

CBT is a structured, evidence-based form of psychological treatment that helps people understand the connection between their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. The core idea is that how we think about a situation affects how we feel and what we do—and that by changing unhelpful thoughts and behaviours, we can improve how we feel.

Some of the key features of CBT include:

Present-focused: It often concentrates on current problems rather than delving deeply into the past experiences.

Goal-oriented: You and your psychologist will set specific goals and work actively towards them.

Collaborative: You work together with your psychologist to understand patterns and try new approaches.

Skills-based: CBT teaches practical skills, such as identifying and challenging unhelpful thoughts, problem-solving, and coping strategies.

Who Is CBT For?

CBT can be a highly effective starting point for people exploring therapy for the first time, and it’s also well-suited to individuals dealing with specific, less complex concerns, where practical strategies can make a noticeable difference in day-to-day life.

Some of the common reasons people in Melbourne seek CBT:

Anxiety: Whether it’s generalised anxiety, panic attacks, or social anxiety, CBT can help people identify and challenge the unhelpful thinking patterns that drive fear and worry. It also supports people to gradually face avoided situations, reduce physical symptoms of anxiety, and build more helpful responses to stress.

Depression: CBT supports people to recognise the unhelpful thinking patterns that often accompany low mood. It helps individuals challenge these thoughts, re-engage with meaningful activities, and respond to difficult feelings in more constructive ways.

Adjustment to life changes: CBT helps people respond to challenging life transitions—like moving overseas, relationship breakdowns or career changes—by identifying the thought patterns that make the change feel distressing, overwhelming or threatening. Through cognitive restructuring and behavioural strategies, CBT can reduce distress, establish more realistic expectations, and help people to approach their circumstances with greater psychological flexibility.

Stress and burnout: CBT can help people to identify the patterns of thinking and behaviour that contribute to feeling overwhelmed, exhausted, or unable to switch off. It supports people to challenge unrealistic expectations, develop healthier boundaries, and build practical strategies for managing demands.

Modified versions of CBT can be also used for a wide range of other presentations, including insomnia, eating disorders, PTSD, and chronic pain and health conditions. Beyond mental health issues, CBT is also widely used to help people improve coping skills, build resilience, and support personal growth. It is a highly effective approach that many people can benefit from.

The CBT Triangle: Thoughts, Feelings & Behaviours

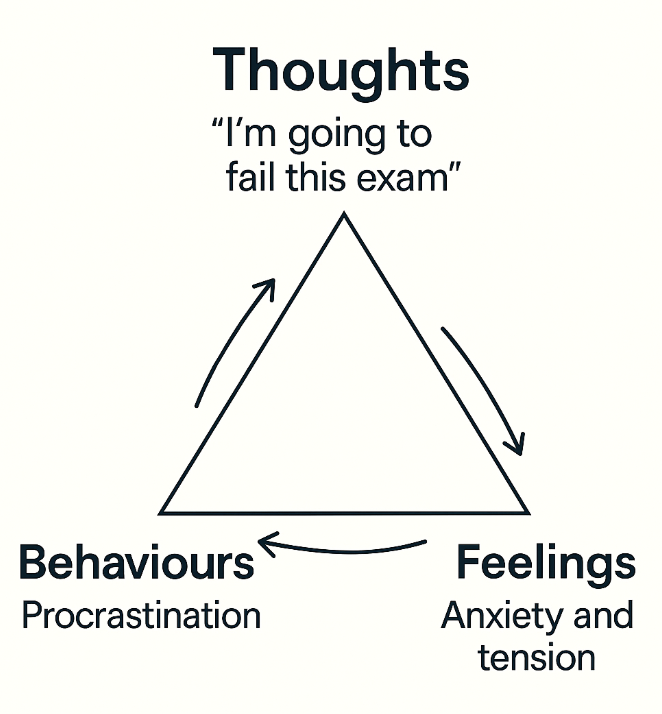

One of the most recognisable tools in CBT is the ‘CBT triangle’, which helps to build peoples understanding of how our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours influence one another.

The CBT Triangle

The triangle shows how our thoughts, emotions, and behaviours interact.

Example Before CBT:

Thought: “I’m going to fail this exam.”

Feelings: Anxiety and tension.

Behaviours: Avoiding study or procrastinating—which reinforces the original fear.

Applying CBT here can help identify and shift the unhelpful thought around failure that is driving anxiety and procrastination into a more balanced or realistic thought.

Example After CBT:

Thought: “I might find some parts difficult, but I will do my best.”

Feelings: Reduced anxiety, increased confidence.

Behaviour: Less avoidance of study—leading to more effective preparation for the exam.

These examples illustrate the core CBT concept of how our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours interact—and how changing one, particularly our thoughts, can lead to positive shifts in the others.

Common Thinking Traps (Cognitive Distortions)

Since thoughts play such a central role in influencing our feelings and behaviours, CBT pays close attention to common thinking patterns that can be unhelpful or distorted. These common thinking traps, known as cognitive distortions, often maintain negative cycles by making our perceptions less accurate or overly negative. Understanding and addressing these distortions is a key component of CBT which helps to shift our thoughts into more helpful or neutral perspectives.

All-or-Nothing Thinking: This is when we view things in extremes. For example, “If it’s not perfect, then I’ve failed.” This leaves no grey area and can make it hard to recognise other perspectives, such as making progress or acknowledging small wins.

Catastrophising: This refers to assuming the worst possible outcome will happen. For instance, “If I make a mistake, I’ll lose my job and won’t recover.” It often starts with a small worry that quickly spirals into a much bigger fear. This kind of thinking can heighten anxiety, leave us feeling overwhelmed, and make it harder to respond calmly or realistically to challenges.

Overgeneralising: This is when we draw broad conclusions from a single negative event. For example, “I didn’t do well in that meeting—so I’m terrible at my job.” One setback becomes proof of a bigger belief, even when the evidence doesn’t support it. Over time, this thinking can reinforce self-doubt and hold us back from seeing things more fairly or realistically.

Mind Reading: This occurs when we assume we know what other people are thinking—and this is almost always something negative. For example, “They didn’t reply, so they must be annoyed with me.” It often leads to unnecessary worry or self-criticism, even without any real evidence. Mind reading can get in the way of open communication and make us feel insecure or disconnected.